The soothing sound of Stern

The Stern Review Report on the economics of climate change is truly fascinating and an excellent contribution... it looks like the work of a small army of über-anoraks.

The Stern Review Report on the economics of climate change is truly fascinating and an excellent contribution... it looks like the work of a small army of über-anoraks.

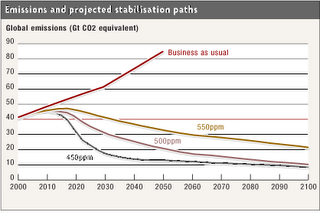

But there's a big difference between the tone and the tome. The launch messages are useful and politically powerful - doing nothing will cost a great deal; passing 550ppm is too dangerous to contemplate; doing something about it is feasible and economically good value; early action saves greater costs and risks later. The tone of the launch was oddly reassuring, suggesting that climate change can be fixed with about 1% of GDP, that's the proceeds of about 3 months of world growth. A bargain, surely, to save us from the savagery of a rapidly changing climate? Broadsheet commentators cheered, relief was palpable, paradigms will be shifting, but only a bit. Sorted!

The 700 page tome is much more unsettling. Take the emissions trajectories (see chart). Even the highest risk scenario that Stern is prepared to countenance has world emissions peaking in just 10 years from now and falling globally by at least 25% by 2050, compared to expected doubling under BAU. This would require a massive overhaul of the world energy and transport economy, agriculture and forestry, and given that many energy sector assets have lives of 40+ years, it means a dramatically different paradigm will need to be established almost immediately and almost everywhere. Existing assets may well be stranded and obsolete. And it's not just investment, but also major changes in behaviour that are required, over which government's do not have total control.

In terms of the response, much was made of the role of emissions trading and the scope for a global carbon market based on an extension of the EU system though Stern wisely proposes using a mix of taxes, cap 'n' trade, and regulation to set a broadly consistent carbon price (Part IV). But a trading system is merely a valuable efficiency measure allowing separation of responsibility for cuts and who actually makes them. The fundamental question is how responsibility is determined... and this is coded into the the initial allocation of 'property rights' - the right to emit carbon - in the system both the total amount and its distribution. Now this really is at the heart of the 'global collective action problem' that Stern has described. (And we should note that poor allocation is the most a conspicuous failure of the EU ETS system - see Oxera discussion - Is the EU ETS Working). The discussion of collective action (see Part VI) is summarised in the conclusions:Countries should agree a broad set of mutual responsibilities to contribute to the overall goal of reducing the risks of climate change. These responsibilities should take account of costs and the ability to bear them, as well as starting points, prospects for growth and past histories.

Er, yes. But that is the very core of the problem, what makes it difficult to negotiate as each party places different weighting on this factors consistent with its perceived interests, and in any really ethically based approach, these principles create huge challenges for the developed countries, rampant over-users of the common global carbon sink... Given this is the heart of the problem, surprisingly little space is spent on exploring it. Buried on p. 475 is a table that discusses burden sharing, and a remark made almost in passing...The results indicate that emissions reductions of 60-90% on 1990 levels by developed countries would be required to meet a stabilisation range between 450 and 550ppm

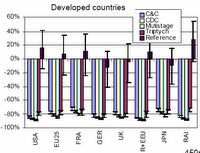

Ninety percent... ouch!! Throughout the report and in the presentation, there seems to have been a determination to accept the UK's target of a 60% cut by 2050 is an adequate goal for developed countries... but also on p.475 is a chart (left) comparing four different ways of allocating the global carbon budget using different principles. As you can see here, the required cuts for the EU are around 80% by 2050 for stabilisation at 550ppm.

Ninety percent... ouch!! Throughout the report and in the presentation, there seems to have been a determination to accept the UK's target of a 60% cut by 2050 is an adequate goal for developed countries... but also on p.475 is a chart (left) comparing four different ways of allocating the global carbon budget using different principles. As you can see here, the required cuts for the EU are around 80% by 2050 for stabilisation at 550ppm.

The report is a very positive development, and Stern himself is part of the response to the global collective action problem. But I think he made it sound a lot easier than it will actually be and hasn't quite provided the blueprint for addressing the collective action aspects of the problem that he set out to do.

3 comments:

I think the Stern Review has struck the right middle ground – I notice that he has both been criticised by some for being ‘too dramatic and doom mongering’ whilst also being criticised by some environmentalists for being too optimistic in assuming that stabilisation could be achieved at around 550ppm. The Government’s backing of 60% by 2050 target – which its now making statutory – is largely predicated on a stabilisation concentration of 550 ppm. But many studies have recently shown that achieving a stabilisation level of 2 degrees would require an emissions concentration of at least 450 ppm. But the implication of that – as you say – is that the 2050 target would require an 80% perhaps 90% cut in emissions. I think we recognise that asking the public and business to accept such as massive cut would be near impossible. We can’t even currently achieve the manifesto target of 20% by 2010 and whilst Stern is optimistic he is being politically pragmatic.

What struck me about the Stern Review was that the ‘economic costs’ of adaptation doesn’t sound all that bad – the additional costs of making new buildings resilient to climate change in the OECD countries is estimated at between 0.05% and 5% of GDP - $15 to $150 billion per year is virtually nothing to developed nations when you put it into perspective. For the UK, the annual flood losses of warming of between 3-4 degrees is actually very small – a cost of 0.2%-04% of GDP by the middle of the century – suggesting we could easily ‘pay’ to adapt to the effects of climate change. Unfortunately, some could therefore use this to interpret that the ‘rich’ developed world therefore needs to do little as ‘we’ll be alright’…. What’s not new is that learning that the real losers will be those in developing countries who will have to deal with the extreme effects of drought and sea level rise and who are less able to bear the costs. The problem that Stern highlights and politics is not well equipped to deal with is that we are in effect asking people in the developed world to make significant changes to their behaviour – purchase less climate impacting products and services and move towards cleaner sources of powering our societies – not necessarily for the benefit of poorer people in developing countries right now – but their children who aren’t even born yet. Try selling that politically.

Greetings Anon...

I agree the report is a good assessment and I think that Stern's 'middle ground' in this debate marks great progress in understanding the risks... My feeling was that the message was just too reassuring - the Chancellor was quick to say that Stern proved that the goal of long-term sustained growth was compatible with fixing the climate. Even if the cost is one percent of GDP (a managaeble £10 billion pa for the UK), the difficulties only begin with this, because there is such tremendous inertia in stock of energy assets and in human behaviour.

I may not have read it properly, but my reading of the section on burden sharing and diagram I reproduced is that a cut of 80% would be required for UK/EU by 2050 to achieve a 550ppm stabilisation using the four methodologies mentioned briefly on p. 474-5, rising to about 90% for 450ppm. It looked to me like the report had been 'reviewed' to make sure it was consistent with UK policy of a 60% cut by 2050 being compatible with its findings. Hence the weakness of this section. Too cynical?

I was drawing attention to that not because I think an 80% cut by 2050 will be possible or good policy, but because it shows why cracking the collective action problem will be so hard... anything remotely fair and applying objective principles to allocating rights to the global carbon sink, will almost certainly cause the shutters to come down in the developed countries. The collective action problems deepen still further when the intergenerational dimension is included, as you point out.

Meanwhile our supposed leadership in this are has barely tamed carbon emissions, which have been rising in the UK - most of our achievement being from the dash for gas in the early 1990s. It makes the 60% cut target look very challenging indeed and will need policy measures far stronger than we have seen so far - and a way of delivering them that does not cause the public to vote out those proposing them. That's a mighty political project! And more than just top slicing one-percent of the economy...

All the same, the Stern Review a terrific advance and I still have much of it to digest.

Thanks very much for all this. If I read it correctly (and please someone correct me if I don't), the Stern Review is quoting as credible an estimate of a 2 to 20% chance of climate sensitivity of greater than 5 C if GHG concentrations stabilised at today's level of approx 430ppm CO2e (part 1, page 9). That is, the Review is suggesting we take seriously the possibility that there is already an up to 1 in 5 chance of an outcome likely to be catastrophic even if all emissions were to stop today.

I agree with what you say about the Gordian knots of collective action and intergenerational equity (much of it for babies that don't even look like "us"). These look like incredibly hard challenges to sell to European, or any, publics. ( I have tried to put a brave face on one aspect of part of one of them with a post titled "China: time for a politics of climate change (2)" at jebin08: http://jebin08.blogspot.com/2006/11/china-time-for-politics-of-climate.html. And it is interesting to read that Margaret Beckett has reportedly been feisty in a similar vein in India - see http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?xml=/news/2006/11/04/nclim04.xml )

I have a lot more to digest in Stern. Does, for example, the Review take account of a range of scenarios of very large refugee flows into Europe (or the costs of keeping people out)? Dealing with blowback from big conflicts resulting from severe water shortage etc in Europe's "near abroad" (Mid East and large parts of Africa) could be more expensive, and more difficult than flood proofing homes in Essex.

Post a Comment