In many ways the IPCC 4th Assessment Report (known by aficionados as 'AR4') from the physical science working group confirms much we had already taken to be established beyond reasonable doubt (see summary). A huge impulse (greenhouse gas increases) is being applied to a complex physical system (atmosphere, oceans and carbon cycle) and modellers are struggling through the task of working out how it will respond... (see charts to the left). To paraphrase Donald Rumsfeld's famous saying, the exercise involves narrowing quantitative uncertainties in the known-knowns, giving qualitative warnings about the known-unknowns and admitting we should still be worried the unknown-unknowns. And worth remembering, Rumsfeld also concluded, albeit in a different context: "it is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones."

In many ways the IPCC 4th Assessment Report (known by aficionados as 'AR4') from the physical science working group confirms much we had already taken to be established beyond reasonable doubt (see summary). A huge impulse (greenhouse gas increases) is being applied to a complex physical system (atmosphere, oceans and carbon cycle) and modellers are struggling through the task of working out how it will respond... (see charts to the left). To paraphrase Donald Rumsfeld's famous saying, the exercise involves narrowing quantitative uncertainties in the known-knowns, giving qualitative warnings about the known-unknowns and admitting we should still be worried the unknown-unknowns. And worth remembering, Rumsfeld also concluded, albeit in a different context: "it is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones."

Suggestions that sea level rise might be lower than previously thought were met with glee in traditionally sceptical quarters... (see: UN downgrades man's impact on the climate in the Telegraph) but these interpretations are confused with a narrowing of the range of uncertainty around a central estimate that is close to the Third Assessment Report in 2001. There are better graphics, clearer communications, new insights, finer resolutions etc - but basically not much different from a policy point of view. I think that may be because the emphasis has been on nailing the so-called sceptics - and therefore on delivering a 'shock and awe' response to tiresomely self-interested sceptics' challenges to conclusions already drawn and largely accepted for policymaking purposes. But I think this might be a bad thing and the IPCC is letting us down...

Does the IPCC do a disservice by being this cautious?

The IPCC provides a gold standard and very high level of assurance - it also has to negotiate text between scientist delegations from countries that may be hostile to a completely truthful exposition. But is there a danger of fighting the last war, and failing to really convey threats? Does this give an implicit victory to the sceptics - who are paid to slow down progress and sow confusion and doubt? Could all this caution and risk-aversion seem like 'good science' but actually have the perverse effect of raising the real risks because they find it harder to include coverage of the known-unknowns and unknown-unknowns? New Scientist magazine suggested this is the case:

The peer review process was so rigorous that research deemed controversial, not fully quantified or not yet incorporated into climate models was excluded. The benefit - that there is now little room left for the sceptics - comes at what many see as a dangerous cost: many legitimate findings have been frozen out. [See: What the IPCC didn't tell us]

The New Scientist article, which is subtitled "If the official verdict on climate change seems bad enough, the real story looks far worse", argues that concern about sceptics and its own status has biased the IPCC in favour of what can be modelled with confidence, or as I would put it, measuring Rumsfeld's 'known-knowns'. In contrast, an excellent conference held in Exeter in 2005 was titled "Avoiding Dangerous Climate Change" and had leading scientists investigate what 'Dangerous Climate Change' would mean and what it would take to cause it. That gives a far more worrying picture - yet much of its substance is ignored or only alluded to in AR4 summary... the modelling has primacy. My concern is that excessive hedging and gold-plating in scientific advice is a form of 'reckless caution' because it leaves decision-makers with an overly sanguine prognosis.

There are nevertheless some very troubling passages in the IPCC summary.

1. All of it

Even just taking the science as established and summarised in AR4 and assuming that is all that is known and all that will ever happen, the prognosis is still very bleak.

2. Sea level rise

AR4 points out that much higher sea levels have been associated with warmer temperatures in the past...

Global average sea level in the last interglacial period (about 125,000 years ago) was likely 4 to 6 m higher than during the 20th century, mainly due to the retreat of polar ice. Ice core data indicate that average polar temperatures at that time were 3 to 5°C higher than present, because of differences in the Earth’s orbit. The Greenland ice sheet and other Arctic ice fields likely contributed no more than 4 m of the observed sea level rise. There may also have been a contribution from Antarctica.

But the range of global average temperature increases projected for the 21st Century is up to 6.4 degrees (for the most fossil fuel intensive) emissions and many highly plausible business as usual scenarios would increase temperatures by 3-5 degrees (see Table SPM3 in the summary p.13) view table

But note that projections for polar warming are higher (especially for the north ) than for the global average - for example, scenario A2 gives a global average warming of 3.4 degrees C by the end of the century, but more than 6 degrees in the polar north. See map (left) from Figure SPM-6 in the summary)

But note that projections for polar warming are higher (especially for the north ) than for the global average - for example, scenario A2 gives a global average warming of 3.4 degrees C by the end of the century, but more than 6 degrees in the polar north. See map (left) from Figure SPM-6 in the summary)

This probably means that temperature rises in the 21st Century will cause a large commitment to sea-level rise - and what remains uncertain is how fast that will occur. The IPCC concedes that this isn't properly understood or included in current models:

Dynamical processes related to ice flow not included in current models but suggested by recent observations could increase the vulnerability of the ice sheets to warming, increasing future sea level rise. Understanding of these processes is limited and there is no consensus on their magnitude.

What if the processes are more rapid and the ice-sheets more vulnerable as suggested by recent observations? There is increasing evidence that the physical disintegration of ice sheets will happen more rapidly than thermal melting.

3. Temperature increases and carbon cycle feedback

Another area that was troubling to me was the discussion of the 'carbon cycle feedback' - that more carbon is retained in the atmosphere as it warms - and this isn't factored into models yet because of uncertainties. The report says this about it:

Climate carbon cycle coupling is expected to add carbon dioxide to the atmosphere as the climate system warms, but the magnitude of this feedback is uncertain. This increases the uncertainty in the trajectory of carbon dioxide emissions required to achieve a particular stabilisation level of atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration. Based on current understanding of climate carbon cycle feedback, model studies suggest that to stabilise at 450 ppm carbon dioxide, could require that cumulative emissions over the 21st century be reduced from an average of approximately 670 GtC to approximately 490 GtC (Summary report p.17 edited here to remove ranges for ease of reading) 1 GtC is a billion tonnes of carbon world carbon emissions including land use changes were 8.6 GtC in 2000 or 11.2GtCe including all other greenhouse gases)

Yikes! that means 490 GtC is very low. And this is troubling, because 450ppm is a figure often used as a threshold for avoiding dangerous climate change (associated with a temperature rise of 2C). And achieving a 490 GtC (billion tonnes of carbon) budget for the 21st Century will be incredibly difficult. This is way below the minimum if the emissions scenarios used for modelling, and supposed to represent the range of plausible emissions trajectories.

Yikes! that means 490 GtC is very low. And this is troubling, because 450ppm is a figure often used as a threshold for avoiding dangerous climate change (associated with a temperature rise of 2C). And achieving a 490 GtC (billion tonnes of carbon) budget for the 21st Century will be incredibly difficult. This is way below the minimum if the emissions scenarios used for modelling, and supposed to represent the range of plausible emissions trajectories.

The charts to the left are from the IPCC special report on emissions scenarios (with my annotations) - these give a range of emissions from 770 GtC to 2,540 GtC. They aren't predictions, but scenarios to help model possible future worlds. The B1 scenarios offer the lowest emissions pathways, and these are built on a 'storyline' of strong sustainable development and localism. The world economy is currently nothing like B1-world, nor is it heading there. So to get to 770 GtC would mean an emissions trajectory following the lower bound of the B2 scenarios as indicated in the bottom of the two charts above. To get to 490 GtC would require the area under the curve to be reduced by more than one quarter.

4. It is only "very likely" that humans are causing global warming - a win for the sceptics

Even if, as I suggested above, the aim of the report is to see off the sceptics, I fear the enterprise may have been lost in the drafting. The report uses a range of terms expressing confidence in its findings. The summary report p.4 footnote 6 says that 'very likely' means more than 90% confidence and 'extremely likely' means more than 95% confidence. The BBC set this out well in its overview of the summary report. The report states that

"Most of the observed increase in globally averaged temperatures since the mid-20th century is very likely due to the observed increase in anthropogenic greenhouse gas concentrations" (original emphasis)

If I was a climate sceptic I think that getting the IPCC to say that there is between a 1 in 10 and 1 in 20 chance that the entire intellectual edifice of man-made climate change is wrong is not a bad effort. That's a degree of uncertainty that cannot be found ANYWHERE in the scientific literature. It is plainly wrong and misleading, but because it is misleading on the side of doubt, they have somehow got away with it.

I gather the Chinese scientific delegation fought alongside the predictable Saudis to keep the 'likelihood' as low as possible. It's easy to see why the Saudis might do this, but much less obviously in even the short term interests of China, which would be hit hard by the impacts and has a good claim to demand action from developed countries with many times the emissions per capita.

5. Decoupling of science and politics

The scenarios modelled by the IPCC are very different to those under discussion in the politics and economics. A footnote (14) on page 10 of the summary report points out that the concentrations of carbon dioxide equivalent could be very high by the end of the 21st century:

14 [...] Approximate CO2 equivalent concentrations corresponding to the computed radiative forcing due to anthropogenic greenhouse gases and aerosols in 2100 ... for the SRES B1, A1T, B2, A1B, A2 and A1FI illustrative marker scenarios are about 600, 700, 800, 850, 1250 and 1550 ppm respectively.

So 600ppm CO2e is the minimum in the IPCC scenarios. This is not new news (and nor are the scenarios forecasts), but it does suggest that the debate on economics and policy may have become detached from the scientific modelling in some important respects - given that the SRES scenarios are supposed to cover the full range of plausible emissions trajectories.

The Stern Review debated at length about whether concentrations need to be stabilised at 450 ppm or 550 ppm CO2e - see Chapter 8 - The Challenge of Stabilisation Stern bases his estimate of the social cost of carbon ($US85/tonne CO2) on 550ppm - it would be higher if the expected concentration was higher.

The European Union's 10 January 2007 initiatives on climate change and energy have restated a goal of limiting warming to 2C over pre-industrial temperatures.

The EU's objective is to limit global average temperature increase to less than 2°C compared to pre-industrial levels. This will limit the impacts of climate change and the likelihood of massive and irreversible disruptions of the global ecosystem. The Council has noted that this will require atmospheric concentrations of GHG to remain well below 550 ppmv CO2 eq. By stabilising long-term concentrations at around 450 ppmv CO2 eq. there is a 50 % chance of doing so [European Commission, Limiting global climate change to 2 degrees Celsius - COM(2007)2].

But the IPPC showed that warming since pre-industrial times has been 0.76C and its projections for the lowest emissions scenario (B1) are a further 1.8C by 2090-2099 compared to today - with a range of 1.1 to 2.9 [view table].So it would only be possible to achieve the EU objective if the future warming was at the very low end of the possible ranges, for the lowest emissions scenario. But even this is not right... the atmosphere will continue to warm after the emissions stabilise or fall well into the 22nd century because of inertia in the system. In other words, it is extremely unlikely that warming will be kept to 2C, even if, in a triumph of hope over experience, we take measures that vastly exceed expectations.

Conclusions

- The AR4 reads to me too much like a rebuttal of the sceptics and attempt at language that cannot be challenged. That is not the same as the best scientific advice to governments. If the IPCC can do only the former (and I wouldn't want it to stop doing that), I think there is more scope for advice that is really intended to be the best possible account of the known-unknowns and best possible speculation on the unknown-unknowns - done if necessary outside the IPCC. Like the 'Dangerous Climate Change' conference, I mentioned earlier.

- I'm glad the world is waking up to climate change and the EU is pushing hard for target that matches the objective of the UNFCCC (see article 2) to "achieve stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system" - I'm also glad that Stern took this approach too. But I wonder if these are at all realistic, even if we are hyper-optimistic?

- I think we need IPCC developing and modelling emissions scenarios that fit interpretations of this objective - such as those produced by Stern and the EU. In some ways the modelling process needs inverting, so that an emissions budget or trajectory is the output of a model in which the impacts on the climate system are constrained to values that would be consistent with the UNFCCC objective.

- The EU could commission its own scientific advice on the required emissions trajectories to meet the environmental constraints (and probably constraints in the maximum rate of adjustment) that it has established in its flagship policy - the EU has a budget of €50.5 for science for 2007-13.

- I think the EU should also commission advice on the harder-to-quantify and difficult-to-model risks (like the Avoiding Dangerous Climate Change publication) and add an additional scientific voice to the IPCC. This would help to create some diversity in the sources and risk aversion of the scientific advice.

- We need to be more pessimistic in thinking about adaptation than the IPCC AR4 modelling would lead us to believe - to take account of those unknowns that don't make it into the models because they can't be quantified - though they may be very real and dangerous.

- I think we should separate our objectives for stabilisation (say 450-550ppm) from our reference scenario for planning for the impacts and adaptation & resilience (probably at least 750ppm). The latter should reflect the path we are actually on and be adjusted when and if we actually move to a lower emissions path.

PS. Worth a look: Caspar Henderson's Grains of Sand blog on all this - and his comments on this post.

... continues. Read full post.

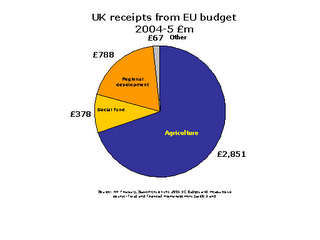

Way past bedtime on 17th December 2005, frazzled European leaders decided how to spend just under one trillion Euro. They set the EU's budget framework from 2007 to 2013 - and committed €947 billion or just over 1% of EU GDP over the period. The chart shows the breakdown of the 2007 budget by major theme - dominated as ever by agricultural subsidies and 'regional' policy or what is now known as 'cohesion' policy (spending in poorer regions of the EU, supposedly to bring them closer to the EU average).

Way past bedtime on 17th December 2005, frazzled European leaders decided how to spend just under one trillion Euro. They set the EU's budget framework from 2007 to 2013 - and committed €947 billion or just over 1% of EU GDP over the period. The chart shows the breakdown of the 2007 budget by major theme - dominated as ever by agricultural subsidies and 'regional' policy or what is now known as 'cohesion' policy (spending in poorer regions of the EU, supposedly to bring them closer to the EU average).